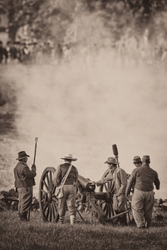

Civil War Reenactments

13th Jul 2020

Many people honor the brave and resourceful people from our past by participating in living history demonstrations known as Civil War reenactments. There are approximately 40,000 Civil War reenactors in the United States. There are also re-enactor organizations around the world, from Europe to Australia. There are actually quite a number of things that make that significant. One is how reenacting has evolved over the last half century. The other is that the items produced for the very first reenactments are now virtually antiques themselves.

Today, perhaps the greatest concern among re-enactors everywhere is “getting it right.” There are entire magazines and newspapers dedicated to just that: reproducing in the finest detail the physical culture, as well as the drill and mannerisms of the Civil War era. Above all, one learns to avoid the dreaded “farb.”

Farb is a re-enactor term meaning unauthentic or inappropriate to the time period. Wearing a wrist watch would be a good example of farb, as would be smoking a filtered cigarette while in period clothes. These are things that could not have occurred at the time, and should not be done while re-enacting. Obviously a pocket watch would be the best choice for time piece, and ideally, one with a key wind. As for smoking, if one must, then a cigar or pipe would be more appropriate.

Just like today, in the early days of reenacting participants prided themselves with weapons and gear. One of the favorite weapons of early re-enactors was the Remington Zouave rifle with matching saber bayonet. Although these are beautiful and well made pieces, it is generally agreed they never saw combat service in the Civil War. But in the 1960’s they were the height of re-enactor fashion. Today, if a re-enactor appeared carrying a Zouave he would find himself a farb pariah.

.png)

There is controversy as to what constitutes farb. An example would be an excess of brass insignia on one's kepi or slouch hat. There are certainly surviving examples of such hats from the Civil War, but were they actually worn that way on the field of battle? Most experts agree that after the first few months of the War between the States they probably were not. So, if you are reenacting First Bull Run, fought on July 21, 1861, you might be laden with sparkling brass. By Gettysburg, fought July 1-3, 1863, it is unlikely that much of your gear would have sparkled, as anything that drew attention to you would have been discarded long before.

Certainly, one aspect of this argument has to do with availability. Initially there were very few choices available for the pioneering re-enactor. Many used original equipment; a surprising amount was still readily available from companies like Bannerman’s, the first great surplus company, which was selling Civil War knapsacks for $1.50 and greatcoats for $15.00 in 1965. Even Civil War swords and muskets were available for under a hundred dollars throughout most of the early days. Thus, some early re-enactors went onto the field wearing USMC dress tunics, and carrying original muskets. This would make most modern re-enactors recoil in horror, both from the “farb” aspect of the tunic, and the idea of a precious original relic, today worth hundreds or even thousands, being endangered on the field.

As reenacting has matured, the impression of the battlefield soldier has actually become plainer and simpler. A basic uniform will consist of frock or sack coat, forage cap, slouch hat or kepi, kersey trousers and brogans. Other than that there is no need for much embellishment. The focus tends to be put in the details of the weapons and, in particular, the personal gear.

When I began reenacting, there were no reproductions of the U.S Model 1842 Musket available. I ended up building one out of a mix of original and reproduction parts, and ended up with the first 1842 carried by our unit. Of course, just about that time, a major company began reproducing them, for about $300 less than I had paid for my pieced together weapon.

If you are an officer or NCO, then you need to have a proper sword. In the 1960’s the answer was to find an original, resulting in much, if not most, of the so-called “battle damage” found on original weapons today. Soldiers in combat frequently left their swords back at camp. Those who actually fought with them would not have been clashing them edge to edge with the enemy. Edge damage is far more likely to be caused by play-acting than by fighting. Fortunately, reproduction swords are rapidly becoming available in great variety, but they all tend to arrive with a bright coat of lacquer, which needs to be removed. On the other hand, you can now find virtually every variety of Civil War sword at incredibly reasonable prices. With some elbow grease, most can be made into quite good replicas of an original.

During the Centennial, it was common to see WWII G.I. gear in camp and Boy Scout knives in the pockets of many of the re-enactors. Today “doing it right” can easily be within reach for the re-enactor on a limited budget. This is in part due to a better appreciation of the experience of the Civil War soldier in the course of the War. At the beginning of the War soldiers went into the field with loads of expensive, fancy, and ultimately useless equipment. By 1862 most soldiers had their gear pared down to a far more basic, and much lighter, load. Big, flashy Bowies had been traded for simple folding knives. Pistols had been discarded. Body armor (yes, there was body armor for sale in the Civil War) had been tossed aside, or used as an improvised skillet. The essential rule was that gear needed to be simple, light, and used daily, or it was discarded.

An excellent example of the kind of item that a soldier in the field would have considered a true necessity are the “Old Fashioned Horn Folder” and “Old Fashioned Bone Folder” offered by Atlanta Cutlery. The examination of relics from literally dozens of Civil War campsites finds virtually identical knives. The Civil War soldier considered similar knives absolutely indispensable. Along with a “housewife” sewing kit, and canteen-half frying pan, they made up the basic household goods of both Billy Yank and Johnny Reb. Interestingly, very similar knives also show up in digs at Revolutionary War encampments as well.

We can never duplicate the experience of the Civil War soldier, nor would we want to if we could, since so many of them died of disease as well as horrible septic wounds. However, we can understand them better through experiencing a little bit of what they lived. Having well-made duplicates of their gear, and understanding their use, is part of creating that understanding.

By Steven M. Crain

Gift Cards

Gift Cards